It is not uncommon to misunderstand how CGT is determined and applied when it comes to the sale of your home or investment property.

As the reality of these tough economic times kick in, and personal budgets reviewed, it may be that you have decided to sell your property, be that the home you live in, or a second home. While you consider this type of asset to have some real value despite the prevailing ‘buyers’ market, a sale of this nature comes with, what may be a relatively hard-hitting, tax implication: Capital Gains Tax (CGT).

CGT is not unique to South Africa, in fact it can be traced as far back as 1913 in the United States. SA therefore could be considered as somewhat late to the party, given its introduction in 2001. It is however widely endorsed by the developed world, with variable inclusions and/or implications. What is common amongst all the nations that impose CGT, is the jargon.

If you read SARS ‘Legal Counsel Income Tax document, Issue 10 (2018), you would be forgiven for being somewhat blinded by the complexity of it all, given its comprehensive data presented in formal language. This document is updated almost every year; however the 2018 version is current.

It is not as complicated as it may first seem, provided you understand some of the terminology, which is especially important when you declare a profit or loss on the sale of a property asset.

What is Capital Gains Tax (CGT)

In simple terms CGT is payable by individuals, trusts and companies to the South African Revenue Service (SARS) when you sell a property that has increased in value since you purchased it, and applies to those purchased on or after October 2001. There is however an exemption that is applied to primary residences; that being the property that the owner lives in on a permanent basis.

Income tax obligation

The bottom-line essential to understanding CGT is to know that it forms part of an individual’s income tax obligations; it is, in other words, not a separate tax, and therefore must be accounted for/declared in the annual income tax assessment (IT34).

What must be made clear however, regardless of when the property was originally purchased, CGT is payable if there is a profit gain on or after 01 October 2001. Should there be a loss on the asset when sold, it still needs to be declared when submitting your annual income tax assessment. The CGT required is however lower than ordinary income tax.

Capital or revenue?

When declaring a gain or loss on a property, and this is where some confusion may understandably occur, the onus is on the seller to prove whether the original purchase of the property was capital or revenue in nature. To understand the difference ask yourself if the property was purchased to intentionally generate a profit. If the answer is yes, the nature of the purchase would be revenue. If the property was purchased as a financial investment, (such as a second home or rental property) it would be capital in nature, and therefore CGT must be applied.

Proof of the capital nature acquisition of the property asset must also be provided if required, to avoid revenue tax (being the short-term expenses spent on the asset over specific periods). Given that many years may pass between acquisition and sale, it is imperative that these documents be kept safe.

Primary or Secondary residence?

A primary residence is considered the home used for personal use; in other words the home you most regularly live in, and this is exempt from CGT, BUT with limitations. SARS considers the sale of your primary home as CGT-exempt up to the first R2-million gain.

Let’s assume you and your partner own a primary residence together. When this primary residence is sold, each of you qualify for an exclusion of R1-million. However this exclusion does not apply to any portion of capital gains made from parts of the home that are used for business (this may be an office set-up or even a rental).

A second home sale has no CGT exemptions, or exclusions, that can be applied.

How profit/loss is determined

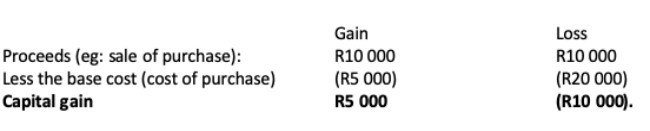

To determine what capital gain has been made, is actually simple math. Deduct the original cost of the property, from the amount that the property was sold for. This will indicate the profit or loss that has been realised.

The terminology used for defining the original cost, is base cost. Base cost includes the original price paid, less all the costs incurred during the ownership period, e.g. renovations, transfer and duties costs, attorney fees, agent’s commission. However if these costs were claimed as expenses in previous years’ income tax assessments, they cannot not be included in the base cost calculations.

To determine the profit or loss, the following example of a basic calculation applies :

Annual Exclusions

As mentioned earlier, CGT is taxed at a lower rate than income tax, which is currently 40 percent, so not the full profit. This derives from the Tax Act which provides a R2-million primary resident exclusion. What this means is if you sell your primary residence, less the base cost, and the profit realised is less than R2-million, you will not attract CGT on the sale of your primary residence.

However if you are selling your investment property, retaining your primary residence, and your gain is greater than the annual exclusion, which is R40 000 for 2019 (and remains so for 2020), it will attract CGT.

Emphasis is on the fact that every individual taxpayer has an annual capital gain exclusion of R40 000, which has to be taken into account when determining the final CGT.

Calculations

A sample of the calculations:

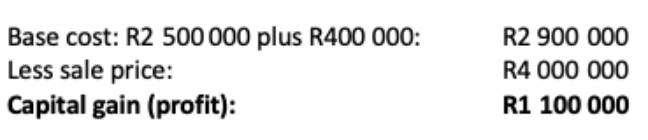

Primary residence scenario:

You buy a home in which you live, for R2 500 000. You spend R400 000 on renovations over the five years. You sell the house for R 4 000 000.

However, because this is your primary residence, and because CGT does not apply to profits under R2 000 000, there is no CGT.

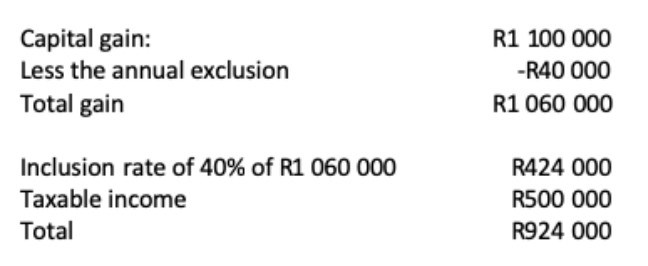

Investment property:

You have decided to sell a second property, which does not have the benefit of a primary residence exclusion; so if your capital gain is greater than the R40 000 exclusion, CGT is now applicable. For the purposes of this calculation, we assume the second property was rented out, and that your taxable income for the year was R500 000. We also need to apply the capital gains inclusion rate of 40% per individual.

The taxable gain (as per the calculation above) on the primary residence must be included:

Assume that the annual marginal rate of tax on income is 41%, which is applied to the R424 000, then the capital gains tax will be R173 840.

These calculations are best handled by using a specific calculator which will guide you through the process, and are readily available online. SARS has also made available on its website, a comprehensive document that outlines all possible scenarios.